Group Assignment for Dr. Elsherief’s EDU 5101: Perspectives in Education

Bushra Pur, Christelle Alida Kenge, Julian Sterling Heidt

We pay respect to the Algonquin people, who are the traditional guardians of this land. We acknowledge their longstanding relationship with this territory, which remains unceded. We pay respect to all Indigenous people in this region, from all nations across Canada, who call Ottawa home. We acknowledge the traditional knowledge keepers, both young and old. And we honour their courageous leaders: past, present, and future.

Indigenous Affirmation from University of Ottawa

What is land-based education, or land-based pedagogy?

Julian Sterling Heidt

An Indigenous land-based education is multidisciplinary and has practical impacts for the real world: science, culture, politics, language, the environment, land rights, reconciliation, and the future of humanity and the planet (McGill University, n.d.). Some examples of these programs are sociolinguistic language revitalization and conservation efforts, Indigenous stories in language arts classes, learning about the environment and ecology through experiential learning experiences through Indigenous communities, experimental science through testing the world by interacting with the land, and much more.

“Land-based education explicitly links experiential learning with Indigenous cultures and ways of knowing and being. While Indigenous pedagogy precedes and exceeds “experiential learning,” land-based educational opportunities integrate some Indigenous connections and teachings explicitly into curricular or co-curricular experiences that might also be understood as experiential. Land-based education takes a variety of forms but always involves an environmental approach to the relationship between people and the land and a recognition of the deep connection between Indigenous peoples and the land” (University of Toronto, n.d., para. 1).

“Land-based pedagogy focuses on Indigenous epistemological and ontological accounts of land, which include a range of practices

and perceptions such as the understanding of land from Indigenous perspectives, land in Indigenous languages and critiques of settler

colonialism” (as cited in Yan et al., 2023, p. 1).

Check below to see our annotated bibliographies on various articles within the extensive domain of land-based pedagogy and education!

Languages, Language Arts, & Liberal Arts

Julian Sterling Heidt

Land-based Pedagogies and Community Resurgence

Corntassel, J., & Hardbarger, T. (2019). Educate to perpetuate: Land-based pedagogies and community resurgence. International Review of Education, 65(1), 87–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-018-9759-1

Corntassel and Hardbarger (2019) provide insight into the Cherokee context in the United States. It is described in the article that a concern within the community is how to best pass on knowledge to the next generation. For example, should language be communicated orally or codified and written down? In which language, Cherokee, or English? Who should have access to the knowledge and processes that help educate future youth? What are the appropriate ontological and spiritual teachings to pass on?

The researchers conducted a multi-component study where the approaches of insurgent research and participatory action research were undertaken to create guidelines (PAR) and strategies of inquiry to answer these questions of what the best approach is going forward.

“[The insurgent research approach] is situated within a larger Indigenous movement that challenges colonialism and its ideological underpinnings and is working from within Indigenous frameworks to reimagine the world by putting Indigenous ideals into practice” (as cited in Corntassel and Hardbarger, 2019, p. 95).

“Participatory action research strives to provide research data to encourage systemic change led by small groups of people for the good of the community concerned. Alice McIntyre outlines three major components of most PAR studies:

(1) the collective investigation of a problem

(2) the reliance on indigenous knowledge to better understand that problem

(3) the desire to take individual and/or collective action to deal with the stated problem”

In line with a focus on praxis, many PAR studies embed community engagement in the research process by creating interactive websites, hosting public community presentations or events, exhibiting work at art shows, etc … This approach, coupled with the photovoice method, is increasingly being utilized in Indigenous communities.“

(as cited in Corntassel and Hardbarger, 2019, p. 95).

The method used was a point of inquiry known as photovoice: “utilizing photography, the goals are to enable people to record and reflect perceptions of community strength and concerns, to promote critical dialogue and knowledge about important community issues through large and small group discussions of photographs, and to reach decision-makers/policy makers. Photovoice draws upon the theoretical underpinnings found in Paulo Freire’s approach to education for critical consciousness, feminist theory, and community-based documentary photography” (as cited in Corntassel and Hardbarger, 2019, p. 95).

There were five participant groups in the study: two groups from a high school and three groups from a university:

(1) 11 Cherokee youth (2 male, 9 female) aged 15-18 at a high school in Stilwell, Oklahoma in 2016 and 2018 (two groups)

(2) 15 Cherokee youth (8 male and 7 female) aged 19-28 in three undergraduate courses in 2016, 2017, and 2018 at Northeastern State University (NSU) in Tahlequah, Oklahoma (3 groups).

The research questions of the study that were answered through the use of photography were:

(1) What values, practice, relationships and/or responsibilities need to be perpetuated to sustain our lifeways as Cherokee people for generations to come?

(2) What are the salient qualities of sustainable communities?

Both groups took photographs individually using the guided research questions in the local area over the span of two and a half weeks. Each participant in the study submitted multiple photographs and described the story or meaning behind each photograph, either orally or by writing. Then individual interviews were conducted for the high school students with their work, while the university students had shared their photographs and storytelling with the entire group.

Three recurring themes resulted from the data were

(1) Responsibility to honour knowledge and continuance

“Responsibility to pass on knowledge (i.e. lifeways, language, traditions) by being a lifelong learner and teacher (e.g. hunting, gardening, gathering and cooking, making quilts, beading, weaving, basketry). All of these serve as distinct acts of perseverance, continuance and representation.” (as cited in Corntassel and Hardbarger, 2019, p. 98).

(2) Family relationships and communal values

“Importance of family and community relationships as a site of learning and support through relationships of dependency. Everybody working together (unity, gadugi, [i..e, working towards a common goa]l), sharing with those unable to participate (support love).” (as cited in Corntassel and Hardbarger, 2019, p. 98).

(3) Relationship to land and water

“Access to and protection of healthy ecosystems that allow for sustainable water- and land-based practices.” (as cited in Corntassel and Hardbarger, 2019, p. 95).

These research methodologies can also be used as a pedagogical approach in the classroom. For example, insurgent research challenges the notion that we must subscribe to a colonial education (choosing materials that expand outside that limiting scope).

Participatory Action Research could be leveraged as an experiential learning opportunity to consult and become involved with the community, such as creating dictionaries and language books through communicating and learning from elders, which for example, could teach sociolinguistics, specifically language documentation and revitalization.

Finally, the photovoice method could be an excellent approach to teach students that a story is more than just the written word and could be a great creative writing activity that can then be connected to the natural world which then explores the subject in more detail (e.g. environment) while analyzing Indigenous poems or stories.

There are many great insights from a research perspective that can be repurposed to an educational one. It also shows what is significant and needs addressing, in not only Cherokee communities, but any Indigenous community.

Learning with the Land: Sixth Graders Restory Interactions with the Land

Yan, L., Isaacs, D. S., Litts, B. K., Tehee, M., Baggaley, S., & Jenkins, J. (2023). Learning with the land: How sixth graders restory interactions with the land through field experiences. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 42, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2023.100754

Yan et al. (2023) researched 39 sixth-grader participants who completed a restorying project on a cross-cultural river trip:

“Restorying is a learner’s rewriting or retelling of a “personal, domain relevant story based on the application of concepts, principles, strategies and techniques covered during a unit or course of instruction” (as cited in Yan et al., 2023, p. 1).

In other words, it is a pedagogical approach that stems from social constructivism where learners make meaning from their experiences and interactions with others; “learners reconstruct, reframe, and elaborate on their own lived experiences through narratives” (as cited in Yan et al., 2023, p. 1).

This practice can be enhanced by using digital tools that afford multiple representations of stories through different modes of meaning beyond merely what they read and write (i.e., think digital storybook, Canva poster, digital comic maker, etc.)

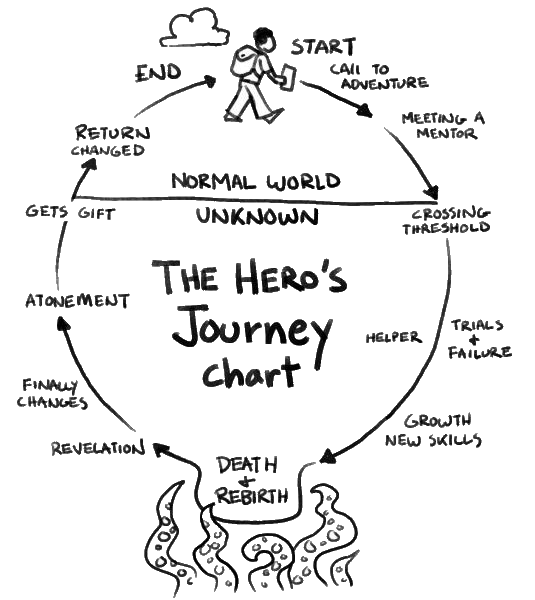

This approach of restorying challenges dominant narratives and allows of complex analysis of meaning making, narrative structure, archetypes, and so on and so forth. After restorying, the students then reflected on the trip through interviews with the researchers.

Every school year, the sixth graders go on a river trip that is a week-long trip with three days on the San Juan River that “serves as a natural border defining the federally forced boundaries of the Navajo Nation” (Yan et al., 2023, p. 3). Each teacher took a different group of students to the trip in turns that encompassed English language arts, social studies, science, and math subject matter. The example for this paper highlighted was for English Language Arts. Teachers partnered with local Navajo guides to provide cultural and ancestral context, as well as participating in respectful land practices, such as collectively pausing and following various cultural protocols before entering a sacred ancestral location where previous Indigenous communities lived. The example provided in the article was explaining how constellations are formed according to Native ontology, and that the rest is not their story to tell. Throughout this trip, these respectful practices formed the groups’ various ways of being (such as camping, rafting, eating, hiking), and served as an overall anchor for learning.

The students have a written assignment after the trip is completed and the prompt for the story was …

“to express their experience on the river trip through the hero’s journey narrative structure.” (Yan et al., 2023, p. 3).

After the students finished drafting their stories, the students made recordings of their stories. The final product from each student included a digital short story collection and a podcast version of their story chapters.

Authors 1 and 2 of the study analyzed the various stories from the students’ submissions by developing and using a codebook to parse information and discover any recurring themes within the data.

It was found through analysis that all students wrote a story centering on coming together, where students focused on individual experiences to develop “interdependent connections with others” (Yan et al., 2023, p. 4).

An exemplar response shows vivid imagery as a result of the intervention, such as describing “a scorching hot sun beating down one one’s skin” and “gloomy clouds in the north of the San Juan River”. Another exemplar demonstrates how various animals belong to different tribes and come together to work as a collective despite their initial reluctance (emphasis on collectivist Indigenous society). The name for a world within the final exemplar is called “Planting Seeds” demonstrating a connection that the student had formed during a pre-trip classroom lesson about Native plants they would see in the area once they arrived in the region.

The three exemplars in order are:

(1) Little Lizard

(2) The North Star

(3) The Girl Who is “Warrior”

By connecting land-based pedagogy with varying story mechanisms, conventions, or other subject matter, teachers can leverage the multidisciplinary nature of a land-based pedagogy that helps students better understand the world around them and question conservative colonial ideologies and dominant narratives, thus, expanding their breadth of knowledge, perspective, and wisdom. An important point to consider is that the three exemplars were written by students identify as White. and the school they come from is 86% White.

There might be a preconceived notion by those not familiar with land-based education to assume that it is meant only for those of Indigenous heritage, but it is for all – as it benefits us understanding a perspective that is not colonizer-focused and in the future creates many more informed citizens of society, which is a transversal skill that can ameliorate relationships between Indigenous and Settler communities and help with reconciliation.

Restoring our Roots: Land-Based Community by and for Indigenous Youth

Fast, E., Lefebvre, M., Reid, C., Deer, W. B., Swiftwolfe, D., Clark, M., Boldo, V., Mackie, J., & Mackie, R. (2021). Restoring Our Roots: Land-Based Community by and for Indigenous Youth. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 16(2), 120–138. https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v16i2.33932

This is pertinent research in our context, as it comes out of Montreal as a joint effort between Concordia University and McGill. The Restoring Our Roots research project follows a Participatory Action Research approach, as described in Corntassel and Hardbarger’s (2019) research.

The research investigated “a four-day land-based retreat…”, formed by an Indigenous youth advisory committee, “… held in July 2018, that focused on reconnecting Indigenous youth to land-based teachings and ceremony” (as cited in Fast et al., 2021). These youth came from Indigenous not-for-profit organizations, college and university Indigenous student centres, and kinship networks.

Following the retreat, Indigenous youth reported positive changes regarding their identity that included or were related to:

(1) Identity

(2) Well-being

(3) Safety (feeling free from violence)

The aspect being researched was to assess the impact of teaching histories of colonialism to Indigenous youth – the goal of this segment of the project was to “better understand how taking part in land-based teachings with other Indigenous youth impacts those involved, and particularly to see if it helped them feel more comfortable continuing on their personal journeys of cultural reconnection” (Fast et al., 2021, p. 125).

“Prior to the retreat, youth expressed pre-existing shame, a desire to feel belonging, and a

sense of exclusion from ceremony due to various barriers, such as gender identity, lack of

access to transportation and funding, school commitments, absence of relationships with Elders, and a general fear of not knowing how to participate. In contrast, many of the youth spoke

about how they felt safe and listened to during the land-based retreat. Being in a safe space and on the land helped the youth manage pre-existing shame and fear of judgment by inviting them into a place of empowerment. The youth spoke about having always wanted opportunities to spend time learning from Elders, participating in ceremonies, and sharing with other Indigenous youth. The themes resulting from the gathering were the following:”

– Inclusion

– Accessibility

– Disconnection

– Reconnection

– Teachings

– Transformation

(Fast et al., 2021, p. 126).

The retreat provided opportunities for video cameras present during open ended questions were given to participants to answer, additionally participants were provided with culturally rich activities, such as art-based sessions where participants made a mixed-media collage, a sweat lodge, sunrise ceremonies, a fancy-shawl (powwow) dancing workshop, storytelling with Elders, a medicine walk, and the blanket exercise followed by sharing circles.

Inclusion: Prior to the retreat, youth often felt excluded from ceremony (with a desire to be included, to connect). When they arrived, they immediately felt welcome and accepted into a larger community.

Accessibility: Many youth want to take part in ceremony (some for the first time ever), however, youth reported lacking accessibility to opportunities in the urban setting. Additionally, their own remote home reserves and communities pose challenges: funding, transportation, scheduling, school commitments, and work.

Disconnection: Youth felt disconnected from their own communities; it was expressed as grief and absence.

Reconnection: The retreat allowed individuals to reconnect with their sense of self, the land, and the community, allowing for more opportunities for growth.

Teachings: Land-based activities and oral narratives were taught at the retreat and helped support the well-being of Indigenous youth, as it provided them with a “newfound sense of purpose, possibility, healing, and gratitude, a distinct realization of responsibility one has to these stories as they carry them through their lives.” (Fast et al., 2021, p. 132).

Transformation: Participants described the retreat as positively affecting them even after they left, “describing the process of integrating what they learned into their day-day-day lives. They expressed gratitude, strengthened identity, and confidence, and excitement to share teachings and knowledge, a personal balance and groundness, humility, hope.” (Fast et al., 2021, p. 132).

In the previous two articles in this section, the emphasis was a land-based learning for all. In this article, the emphasis is placed on the Indigenous community.

With assimilation being omnipresent threat among many communities, it is imperative that culture is preserved not only for the sake of remembering but for connection as well, as this study underscores. Many youths in this study reported feeling disconnected, excluded from their community, or unsafe due to their identity (e.g. Two-Spirit, non-binary, LGBTQIA+). It is stressed by this study that there is a need to create safer spaces, as these groups are an especially vulnerable population (Fast et al., 2021). It is not all about knowledge; it is also about the affective aspects of being seen, heard, and present.

Using the two other previous studies could also be helpful in making future retreats in the way they experientially engage with learners.

Holistic Wellbeing & The Sciences

Bushra Pur

Promoting Health and Wellness through Indigenous Sacred Sites, Ceremony Grounds, and Land-Based Learning: A Scoping Review

Sinclaire, M., Allen, L. P., & Hatala, A. R. (2024). Promoting health and wellness through Indigenous sacred sites, ceremony grounds, and land-based learning: A scoping review. AlterNative : An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 20(3), 560-568.

In this article, Sinclaire et al. (2024) conduct a scoping review to investigate the significance of sacred Indigenous sites, ceremonial practices, and land-based learning in fostering health and wellness within Indigenous communities. The review compiles literature that highlights the critical role these elements play in promoting mental, physical, and spiritual well-being. The authors illustrate that engagement with the land, sacred sites, spirituality, and participation in ceremonies not only aids in the preservation of traditional knowledge but also provides mental health benefits by reducing stress, enhancing resilience, and cultivating a deep sense of cultural identity and belonging.

Sinclaire et al. (2024) analyze research from various Indigenous communities across North America, considering factors such as the impacts of colonization, historical trauma, and cultural resilience. The authors demonstrate how these land-based practices reinforce Indigenous cultural traditions, create opportunities for healing, and tackle issues like depression, anxiety, and substance abuse, which are often intensified by generational trauma. By presenting evidence that ceremonies and land-based learning contribute to improved mental health outcomes, this article underscores the importance of integrating Indigenous wellness practices into broader health frameworks.

Sinclaire et al. (2024) advocate for a holistic and culturally sensitive approach to health services that respects Indigenous cultural practices and emphasizes their importance in health and wellness.

Returning to Our Roots: Tribal Health and Wellness through Land-Based Healing

Johnson-Jennings, M., Billiot, S., & Walters, K. (2020). Returning to Our Roots: Tribal Health and Wellness through Land-Based Healing. Genealogy, 4(3), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4030091

In this article, Johnson-Jennings et al. (2020) explore the role of Indigenous land-based healing in promoting health and wellness within tribal communities. The article outlines the historical context of how colonization has disrupted Indigenous connections to their ancestral territories, impacting both health and identity. The authors, who are Indigenous scholars specializing in health, psychology, and tribal health policy, highlight the cultural and therapeutic advantages of reconnecting with the land, especially for Indigenous groups affected by intergenerational trauma and marginalization. Through an examination of case studies and tribal initiatives, the authors illustrate how land-based practices—such as traditional hunting, gathering, and ceremonies—function as culturally relevant methods for achieving mental, physical, and spiritual healing.

Additionally, Johnson-Jennings et al. (2020) discuss current challenges, including restricted land access, climate change, and legal barriers, that impede the implementation of land-based healing practices in Indigenous communities. The authors advocate for systemic support of Indigenous-led health initiatives that incorporate land-based strategies, which they argue are in harmony with Indigenous worldviews and foster resilience, identity, and overall well-being.

The Role of Māori Community Gardens in Health Promotion: A Land-Based Community Development Response by Tangata Whenua, People of Their Land

Hond, R., Ratima, M., & Edwards, W. (2019). The role of Māori community gardens in health promotion: a land-based community development response by Tangata Whenua, people of their land. Global Health Promotion, 26(3), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975919831603

In this article, Hond et al. (2019) examine the role of Māori community gardens in enhancing health and well-being within Māori communities through a land-centered, community-oriented approach. The authors, experts in Māori health and community development, highlight how these gardens align with Māori cultural values and serve as a means of cultural revitalization, connecting individuals to their ancestral lands and traditional knowledge. They argue for the importance of culturally relevant, community-driven health initiatives, showcasing how Indigenous practices like community gardens can enhance health promotion. The article outlines the benefits of these gardens, which provide healthy food, foster social unity, facilitate knowledge exchange, and support cultural healing. Beyond food production, they serve as spaces for intergenerational learning of traditional gardening methods and spiritual practices, helping to heal historical traumas from colonization.

Hond et al. also discuss key Māori health principles—whānau (family), wairua (spirituality), and whenua (land)—and their significance in health strategies (2019). Additionally, the authors discuss the challenges faced in sustaining these gardens, including securing funding, institutional barriers, and overcoming the limited access to land, which sometimes hinders the expansion of these health initiatives.

Connecting to Praxis

Julian Sterling Heidt

The research from the previous section paints a good picture of how environment, nature, and culture can be used to teach towards biology, science, and ecology. In order to consolidate this point, I’d like to highlight a chapter from a book that I had to read for a university lecture called Learning the Grammar of Animacy by Robin Wall Kimmerer from her book, Braiding Sweetgrass. Kimmerer is a professor at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, and a citizen of the Potawatomi Nation.

I greatly enjoyed her work, and I have since used the very same chapter for my own teaching in my English Language Arts class to provide insight into land-based education and how our understanding of culture and language influences our perception of the world. The chapter is about Kimmerer’s journey and struggle in learning the language of her heritage, Potawatomi. She talks about how her language is endangered, and how the language offers a precision that at times is lacking within our own vernacular – that the Potawatomi language helps promotes a stronger connection to nature by seeing animacy, and how she uses animacy to help teach her students ecology, as it helps us remain mindful that the Earth is a living being. Within the chapter, Kimmerer alludes to Marilou Awiakta’s When Earth Becomes an “IT” when a student picks up on how animacy shifts our perspectives.

When Earth Becomes an “It”

by Marilou Awiakta

When the people call the Earth “Mother,”

They take with love

And with love give back

So that all may live.

When the people call Earth “it,”

They use her

Consume her strength. Then the people die.

Already the sun is hot

Out of season.

Our Mother’s breast

Is going dry.

She is taking all green

Into her heart

And will not turn back

Until we call her

By her name

While the poem alludes a very significant message, Kimmerer makes it clear in her chapter that because in Potawatomi that many words are living. Whereas in English we refer to an ocean as an inanimate being, it, Potawatomi speakers would describe it as a living entity, akin to he or her. Kimmerer uses this concept within her teaching of ecology:

“One afternoon, I sat with my field ecology students by a wiikegama, and shared with them this idea of animate language. One young man, Andy, splashing his feet in the clear water asked the big question. “Wait a second,” he said as he wrapped his mind around this linguistic distinction [of animacy]. Doesn’t this mean that speaking English, thinking in English, somehow gives us the permission to disrespect nature? By denying everyone else the right to be persons? Wouldn’t thins be different if nothing was an “it?” I wanted to give him Awiakta’s poem, When Earth Becomes an It” (Kimmerer, 2014, pp. 56-57).

“Our toddlers speak of plants and animals as if they were people, extending to them self and intention and compassion – until we teach them not to. We quickly retrain them and make them forget. When we tell them that the tree is not a “who,” but an “it,” we make that maple an object, we put a barrier between us. We set it outside our circle of ethical concern, of compassion. “It-ing” [sic] another being absolves us of moral responsibility and opens the door to exploitation. Saying ‘it’ makes a living land into ‘natural resources.’ If maple is an “it,” we can take up the chainsaw. If maple is “she,” we have to think twice” (Kimmer, 2014, p. 57).

There is a linguistic phenomenon known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis where it is believed that language influences perception of the world. It has two versions: linguistic relativism and determinism. The name of the theory derived from Edward Sapir, the mentor, and his student Benjamin Lee Whorf.

This is a practical example of how small of an effort is needed to be made to incorporate a land-based education in one’s classroom, and that they can highlight how science, ecology, linguistics, and humanities all blend together to create a tapestry that is rich with pedagogical value.

Learning from Nature

Christelle Alida Kenge

A qualitative analysis of pupils’ and teachers’ views.

Marchant, E., Todd, C., Cooksey, R., Dredge, S., Jones, H., Reynolds, D., Stratton, G., Dwyer, R., Lyons, R., Brophy, S., & Dalby, A. R. (2019). Curriculum-based outdoor learning for children aged 9-11: A qualitative analysis of pupils’ and teachers’ views. PloS One, 14(5), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212242

This study explores the perspectives of pupils and teachers on curriculum-based outdoor learning for children aged 9-11. Through interviews and focus groups, the research highlights improvements in pupils’ engagement, concentration, behavior, and overall health and well-being resulting from outdoor learning experiences. Teachers also reported increased job satisfaction. The findings suggest that outdoor learning enriches the educational experience by fostering a deeper connection to the material and enhancing cognitive and affective outcomes. Marchant, Todd, Cooksey, Dredge, Jones, Reynolds, and Lyons (2019), in their study Curriculum-based outdoor learning for children aged 9–11: A qualitative analysis of pupils’ and teachers’ views, examined the experiences and perspectives of children and teachers engaged in outdoor curriculum activities. Using qualitative interviews and focus groups, the researchers found that outdoor learning positively influenced student engagement, concentration, and behavior. Teachers reported higher job satisfaction, emphasizing that outdoor learning provided a refreshing change from traditional classroom settings. The study’s insights align with experiential learning theories that advocate for engaging students in active, hands-on activities for deeper cognitive and emotional development.

This source enriches the discourse on Experiential Learning and Connection to Nature by illustrating the direct benefits perceived by educators and students. A notable strength is the qualitative methodology that captures in-depth, subjective experiences, providing nuanced insights into how outdoor learning impacts school dynamics. However, the findings might be context-specific, as they are drawn from a particular age group and cultural background. Despite these limitations, this study underscores the practical advantages of integrating outdoor learning, aligning with the broader push for experiential, nature-based educational methods.

Effects of regular classes in outdoor education settings: A systematic review of students’ learning, social and health dimensions.

Becker, C., Lauterbach, G., Spengler, S., Dettweiler, U., & Mess, F. (2017). Effects of regular classes in outdoor education settings: A systematic review of students’ learning, social and health dimensions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(5), 1-20.

This systematic review examines the impact of regular outdoor education classes on students’ learning, social interactions, and health. The analysis of multiple studies indicates that outdoor learning environments contribute to enhanced cognitive performance, improved social skills, and better physical health among students. The review underscores the multifaceted benefits of integrating nature-based experiences into the educational curriculum, promoting holistic development.

Becker, Lauterbach, Spengler, Dettweiler, and Mess (2017) conducted a systematic review titled Effects of regular classes in outdoor education settings: A systematic review on students’ learning, social and health dimensions. This review synthesized findings from 13 studies exploring how regular outdoor education impacts students’ learning, social interactions, and overall health. The analysis revealed that outdoor education positively influences students’ cognitive development, social skills, and physical health. The review highlights that students benefit from hands-on experiences that foster engagement and a sense of community. Despite these advantages, the authors noted variability in the methodological quality of the included studies, calling for more rigorous research to confirm the findings consistently.

This review is invaluable for the theme of Experiential Learning and Connection to Nature, as it consolidates evidence that supports outdoor learning as a multifaceted educational tool. The strengths of this source lie in its comprehensive approach and ability to link outdoor learning with varied dimensions of student development. However, the limitation regarding the methodological consistency across studies indicates a need for caution when generalizing the findings. Nonetheless, this review effectively advocates for the incorporation of nature-based learning practices in educational settings to promote holistic student development and well-being.

Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue.

Li, D., & Sullivan, W. C. (2016). Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue. Landscape and Urban Planning, 148, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.12.015

This research investigates how exposure to natural landscapes within school environments affects students’ recovery from stress and mental fatigue. The study found that students with views of green spaces experienced quicker recovery times and improved cognitive functioning compared to those without such views. The findings highlight the importance of incorporating natural elements into educational settings to support students’ mental health and cognitive performance.

Li and Sullivan’s (2016) study focuses on school landscapes and recovery from stress and mental fatigue; they explore the relationship between classroom views and students’ mental recovery. The researchers conducted an experiment with 94 high school students, allocating them to classrooms with different window views—no window, a view of built environments, or a view of green landscapes. The study used cognitive tests and physiological measures (e.g., skin conductance and heart rate variability) to evaluate recovery after typical school activities. The findings indicated that students with views of green landscapes experienced quicker recovery from stress and improved cognitive performance, suggesting that incorporating nature into educational spaces can enhance student well-being and attentional functioning.

This study is particularly relevant for understanding the broader theme of Experiential Learning and Connection to Nature, as it provides empirical evidence of the cognitive and affective benefits of environmental exposure. The strengths of the research include its controlled experimental design and the use of objective physiological measures to support findings. However, the study is limited by its small sample size and focus on high school students, which may affect generalizability to other age groups and settings. Despite this, Li and Sullivan’s work underscores the importance of integrating natural elements into school environments as part of an experiential learning approach, contributing to a more holistic view of education that values not just academic outcomes but mental health and well-being.

Conclusion

Julian Sterling Heidt

There is so much to land-based learning and pedagogy that this barely scratches the surface. An important takeaway is that land-based learning is advantageous to all, as it promotes a more informed and educated public. Finally, land-based pedagogy provides meaningful experiential learning opportunities that ultimately improve the quality of our teaching by drawing inferences making many connections to mother nature and the history of the land.

Megwetch! Thank you for taking the time to look over our group project.

References

Becker, C., Lauterbach, G., Spengler, S., Dettweiler, U., & Mess, F. (2017). Effects of regular classes in outdoor education settings: A systematic review of students’ learning, social and health dimensions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(5), 1-20.

Corntassel, J., & Hardbarger, T. (2019). Educate to perpetuate: Land-based pedagogies and community resurgence. International Review of Education, 65(1), 87–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-018-9759-1

Fast, E., Lefebvre, M., Reid, C., Deer, W. B., Swiftwolfe, D., Clark, M., Boldo, V., Mackie, J., & Mackie, R. (2021). Restoring Our Roots: Land-Based Community by and for Indigenous Youth. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 16(2), 120–138. https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v16i2.33932

Hond, R., Ratima, M., & Edwards, W. (2019). The role of Māori community gardens in health promotion: a land-based community development response by Tangata Whenua, people of their land. Global Health Promotion, 26(3), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975919831603

Li, D., & Sullivan, W. C. (2016). Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue. Landscape and Urban Planning, 148, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.12.015

Marchant, E., Todd, C., Cooksey, R., Dredge, S., Jones, H., Reynolds, D., Stratton, G., Dwyer, R., Lyons, R., Brophy, S., & Dalby, A. R. (2019). Curriculum-based outdoor learning for children aged 9-11: A qualitative analysis of pupils’ and teachers’ views. PloS One, 14(5), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212242

McGill University (n.d.). Land-based Pedagogy. https://www.mcgill.ca/walkingalongside/curriculum-pedagogy/land-based-pedagogy

Johnson-Jennings, M., Billiot, S., & Walters, K. (2020). Returning to Our Roots: Tribal Health and Wellness through Land-Based Healing. Genealogy, 4(3), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4030091

Kimmerer, R. W. (2014). Braiding sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions.

Sinclaire, M., Allen, L. P., & Hatala, A. R. (2024). Promoting health and wellness through Indigenous sacred sites, ceremony grounds, and land-based learning: A scoping review. AlterNative : An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 20(3), 560-568.

University of Toronto (n.d.). Land-based Education. https://experientiallearning.utoronto.ca/learningtype/land-based-education/

Yan, L., Isaacs, D. S., Litts, B. K., Tehee, M., Baggaley, S., & Jenkins, J. (2023). Learning with the land: How sixth graders restory interactions with the land through field experiences. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 42, 100754-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2023.100754